A scene from the field

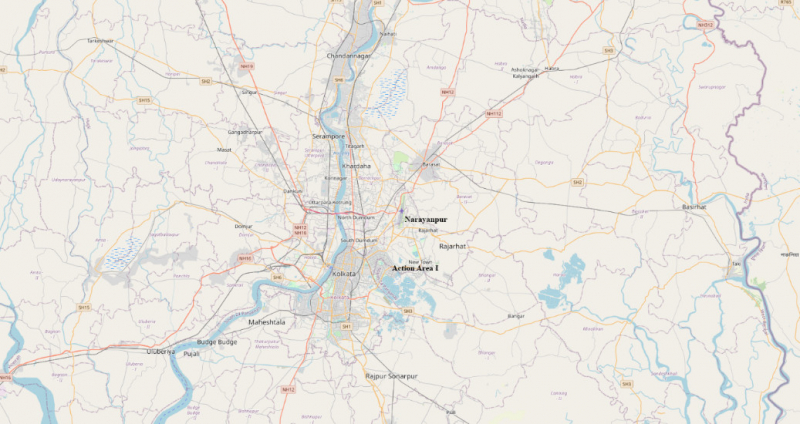

Early in my fieldwork in which I planned to study the planned, developing city of New Town in the state of West Bengal in eastern India, I was looking for the right location to rent a house where I could base myself during the fieldwork. The more developed and relatively bustling neighbourhoods around Action Area I1 (see Figure 1) had a significantly higher rental price. As I was seeking a place to rent on a relatively small budget, I considered visiting some of the properties advertised in classifieds situated outside the planned zone of New Town. My intuition was that the rent in the zones beyond the planned zones of New Town would have lower rental prices. I thought that if I could position myself correctly on a route with public transport, I could access both planned as well as the unplanned areas beyond the planned zone.

In the month of April in 2017 with the approaching hot summers of Kolkata coupled with its humidity, I ventured towards New Town to look for a house accompanied by a friend who wished to explore the eastern parts of the urban agglomeration. I first went to New Town and visited two of the main intersections of the city to comprehend the distance that I would have to travel from the rented lodging. I had already scheduled an appointment with a landlord of a property. As we approached Naraynpur (see Figure 1) after considerable difficulty, switching buses and navigating unknow narrow roads, I realized that the place would not be the right location to live during the fieldwork, as it was cut-off from New Town with a lack of public transport despite the neighbourhood being very close to New Town. Narayanpur, as I found out later, was relatively better connected to its western parts while public transport to the south, towards New Town, was amiss.

Figure 1 : Map of the Kolkata Metropolitan Region with Action Area I and Narayanpur in written in black.

© OpenStreetMap contributors

The landlord, who was an older person in his sixties, came to the main intersection of the neighbourhood to walk us back to his house. While walking towards his house, he inquired about my need to rent a house in the neighbourhood and my profession. I told him about my research in broad strokes and that I was affiliated to a university in Mumbai. I also mentioned to him that I would need to travel to New Town often to which he suggested that it would be a difficult thing to do due to a lack of public transport. The friend who had accompanied me was affiliated to a state-university in the southern part of Kolkata. The old man noted in passing that a neighbour was a faculty at the university and is now retired and lives here.

As the old man and my friend started conversing, my friend noted, gazing around the streets and buildings, that the neighbourhood « feels like a mofussil » and was different than what we had witnessed in New Town just an hour or two ago.

The landlord did not take my friend’s comment lightly. « Not really, the place falls under the Vidhan Sabha2 constituency of New Town Rajarhat », the old man responded. After the walk to the house and checking out the place, I told him that it would be difficult for me to travel to New Town from this spot so I might not rent the place. He remarked that his nephew, who now works in Bengaluru, owns an apartment in New Town, near Action Area I which he rents out. As we left the house and the neighbourhood, a long journey awaited us to take us back to Kolkata.

Of mofussil and New Town

For heuristic purposes, I will limit myself to the exchange between my friend and the old landlord. Here, I am particularly interested in my friend’s utterance and signification of Narayanpur as a mofussil expressed in an affective register wherein, he articulates it as a feeling and the old man’s retort to the statement.

It is important to note that my friend, at that moment, resided in the southern parts of Kolkata but had grown up in the former French enclave of Chandannagar (see Figure 1) which is at a considerable distance from the urban centres. For my friend, who had lived in similar suburban neighbourhoods, the word mofussil is colloquially used to signify such obscure neighbourhoods but the word also carries negative connotation as it is a « relative term » (Hoek, 2012, p. 29) when used by city dwellers from the metropolitan centres.

« Mofussil or “the Provinces” has been defined as the country stations and districts, as distinguished from the “the Presidency” or the centre/capital. Mofussil, however, also refers to the rural localities of a district as distinguished from the sudder or chief station, which is the residence of district authorities. In other words, mofussil has come to signify margins of the metropolis, whether they are small towns distinguished by their curious combination of urbanity and rusticity, or villages existing outside all traces of urbanity. » (Roy, 2009, p. 162)

Mofussil, thus, is a relative term, a term whose utterance relativizes space, i.e., it compares, contrasts and evaluates, in the process foregrounding the relational quality of space. The paper contends that it is precisely such valuations of the world which necessitate an engagement with the scalar debate.

Mofussil essentially refers to spaces other than the metropolis even if they display a degree of what Sassen (2005) calls « cityness ». Though the roots of the word refer back to the colonial times, the word is still a particularly vital lens through which people value and make sense of their and other’s location in the world. There is no agreed upon definition of what a mofussil is anymore as the conversation displayed. But at the same time, it certainly refers to something that can be felt, an affective atmosphere (Anderson, 2009) which is distinctly different than the metropolitan centres.

For the friend accompanying me, mofussil was the signifier that made sense of the feeling of the neighbourhood. However, for the old landlord, mofussil couldn’t capture the governmental classification of the place. Narayanpur voted for the same Vidhan Sabha constituency as New Town i.e., the representative of Narayanpur to the provincial government (state government) was the same as the one who represented New Town.

New Town, for the landlord, wasn’t restricted to the limits of the planning zones or how atmosphere (Anderson, 2009) and the infrastructure (Larkin, 2013) around it looked and felt like. New Town’s planning and development, which led to the land acquisition of swampy agrarian lands close to Narayanpur, had transformed the imaginaries for someone living in this neighbourhood as well. The planning and development of New Town meant that the neighbouring locations had moved out of the classificatory power of mofussil.

The above interaction illuminates the spatial problematique but it also illuminates the scalar problematique and its « search for conceptual tools and methodological strategies adequate to deciphering emergent rescalings » (Brenner 2019, 16). The word 'scale' is used in common, everyday discourse with a variety of meanings. When using phrases such as 'scale of the issue', it refers to a certain 'scope', 'gravity', 'importance' of the issue in question wherein the spatiotemporality of the issue is brought under light. Another common usage of scale is as a tool of measurement, the very act of dissecting reality into arbitrary pieces for analysis. Scale then can be thought of as that abstract process through which humans make sense of their place in the world (Carr and Lempert, 2016).

Considering that mofussil, New Town, Narayanpur, governmental classification etc. are all scalar distinctions in the sense that they exist in a relational network of valuations with some degree of coherence, it becomes evident that scales and the processes of scaling are primarily overdetermined effects and are frames through which actors in the field make sense of their place relationally. I stress on the overdetermined quality of scale-as-effect to distinguish it from both the older positivist conceptions of scale as simply out there and the older Marxist strains of scalar conceptualizations which have a tendency to only consider ‘national’, ‘global’, ‘urban’, ‘region’ as categories worthy of the status of scale.

The above scalar relationalities coalesce in both their singularity, articulated by an individual while at the same time point towards effects which are supra-individual. The old man, when he speaks of Narayanpur transforming away from a mofussil, is not just making an individual statement to locate himself and the place around him but also problematizing the very notion of what constitutes a mofussil and a non-mofussil. To do that he does not evoke sentiments and feelings but evokes a certain relationship of the state, the place, the citizens etc., and their reconfiguration. By doing so, he is interrogating not just what a moffusil is but is also trying to determine the boundaries of New Town and its internal and external relationalities.

Before I develop this reading and link it with the scalar concern, a discussion regarding the existing literature around scale is important and how interfacing that debate with sociology allows us to make sense of the scalar processes in the above scene from the field.

Scalar debate: A recap

Literature on scale is vast and the debate now ranges four decades. Hence, it is worth clearing the ground to locate my argument precisely among the existing constellation of literature that already exists. However, because of the vastness of the literature, I make no pretension of engaging with the wide variety of the literature and its diverse arguments3. After a brief overview, I limit myself to a discussion of the two landmark moments in the scalar debate, the publication of Marston (2000) and Marston et al. (2005), following which in the next section I link the concerns to the discipline of sociology.

Scale before the 1980s was a largely taken-for-granted concept used to organize the natural and social world in the discipline of geography (Herod, 2010). Taylor’s 1981 paper is marked as the foundational moment in the scale literature in critical geography, the moment that would initiate a scholarly pursuit around scale. The paper presented a materialist albeit a « somewhat functionalist approach to scale » (Herod, 2010) wherein Taylor classified the three scales, of urban, national, and the global as « scale of experience », « the scale of ideology » and « the scale of reality », respectively (Taylor, 1981, p. 6-8). Taylor’s engagement with scale lasted throughout the decade and beyond as he persisted in the Marxist and materialist approach towards scale (see for example, Taylor, 1982, 1987, 1997).

Around the same time, Smith (1982, 1984/2010) started interrogating scale from a different perspective albeit retaining a Marxist focus on capitalism. « If, for Taylor, the key questions were what roles various scales play under capitalism, for Smith they concerned how the various scales at which capitalism is organized came into existence » (Herod, 2010, p. 8). As Jones et al. (2017) noted, Smith did not « assign a specific and allied social process to different scales (e.g. ideology to the nation state, experience to the urban) » instead argued that « capitalism produces scales at all levels » (p. 150). The urban scale for Smith (1984/2010) was conditioned by the 'travel to work area', the 'national' scale emerged through capitalists seeking some form of protection from the volatility of global capital, while the 'global' scale emerged out of the capitalist process of normalizing wage labour. This initial theoretical development in the literature was followed by proliferation of texts and discussions around scale with a wedge « between materialists and idealists – about spatial scales’ ontological status » (Herod, 2010, p. 13), concerning whether scales mere mental contrivances or whether they actually existed out there.

Parallel to this development, in the 1980s and 1990s, postmodern, poststructuralist, and feminist influenced works were already using various scalar and spatial metaphors without engaging with the scalar or spatial literature per se. Metaphors such as « “subject positionality,” “mapping,” “location,” “place,” “marginal spaces,” “sites of identity,” “crossing boundaries,” “giving space” for alternate voices, “grounding” » (Herod, 2010) were prevalent and still are. The use of spatial metaphors did not result in this set of literature having a direct influence. Smith & Katz (1993) attribute this to the then un-reflexive character of the disciple of geography which failed to engage with the changing imaginations of space. At the same time, they argue that the literatures which deployed spatial metaphors such as above failed to engage with the materiality of space and scale and left the ghost of absolute space unaddressed, making space a mere container.

By the end of the 1990s, Brenner (1998) classified five broad trajectories in the literature that had amassed by then, 1) « methodological debates concerning the appropriate spatiotemporal unit of analysis and level of abstraction » (p. 460), 2) « reconfigurations of scalar organization (processes of “re-scaling”) » (p. 460), 3) « importance of scale for strategies of social and political transformation » (p. 460), 4) « metaphorical weapon in discursive - ideological struggles » (p. 460), and 5) « political construction of scale » (p. 460).

The debates in the 1990s thus revolved around the reassessment of the productive as well as constructed nature of scale in the field, by actors in the field and by the researchers themselves. It was the publication of Marston (2000) and Marston et al., (2005) that would shift the axis of the debate. By the end of the decade, the terrain of the debate altered considerably. This can be gauged by the conclusive overview of the scalar debate in Herod (2010) in contrast to Brenner (1998).

Herod (2010) classified the different trajectories of the debate to map a state of the affairs. The concerns had shifted significantly to include, 1) the « question of whether or not scale is actually a useful analytical category » (p. 250), 2) the « issue of scale’s materiality (or lack thereof) » (p. 251) 3) « the question of the relationship – if any – between different scales » (p. 252) 4) « how scales are represented – as areal or as networked – and how they actually are », (p. 252) 5) the stickiness of scales, 6) « how the social production of scale is linked to the broader production of the geography of capitalism (or any other social/economic system) » (p. 254) , 7) to « avoid any kind of scalar fetishism wherein certain scales are associated with particular characteristics » (p. 254), 8) the fact that « scales’ significances vary across time and space » (p. 255) and 9) the « relationship between geographical scale and the production of knowledge » (p. 256).

The marked shift in the debate concerning scale is visible in the comparison between Brenner’s (1998) and Herod’s (2010) overview of the literature. While in the late 90s, the debate was still concerned with construction, production and reconfiguration of scales challenging the older positivist underpinnings and the methodological concern of appropriate unit of analysis. By the end of 2000s, the debate had become significantly nuanced, abstract and metaphysical wherein it was interrogating the ontological and epistemological nature of scale and also the methodological efficacy of scale among other concerns. This is not to argue that the works in previous decades did not consider or attempt to engage with such issues. Many of the issues that Herod (2010) summarizes have their roots in older literature from previous decade hence a neat division would not be correct. The intent rather is to evoke the change in the stakes of the debate in the 2000s.

The publication of Marston’s (2000) paper set off a debate which culminated in a few years in the publication of Marston et al. (2005) which altered the terms of the debate and the axes of the debate forever. Marston (2000) argued that the scalar literature failed to properly engage with or conceptualize scales and spaces beyond that of capitalist production that is, the scales other than the canonized scales of ‘urban’, ‘global’, ‘nation’ and ‘region’. To that end, she pushed forward the strand of the literature advocating social construction and production of scales by highlighting the « processes of social reproduction and consumption » (Marston, 2000). Empirically, she brought into focus the scale of the 'household', noting that « Nineteenth-century middleclass women altered the prevailing “Gestalt of scale” by altering the structures and practices of social reproduction and consumption. The scale transformations that were enacted were profound, with effects that reached out beyond the home to the city, the country and the globe » (Marston, 2000).

Brenner (2001) did not take Marston’s feminist intervention kindly. Brenner went on to argue, citing Marston (2000) as the primary example, that a tendency had emerged to deploy the concept of scale where it was not required, conflating scale with other geographical units such as territory, site, space, place, location etc. Brenner's argument hinged on the notion that scales are always relational and hence plural studies need the concept of scale but singular studies are involved in merely studying a socio-spatial phenomenon. For Brenner, distinguishing 'politics of scale' from 'politics of territory', 'politics of place' etc. was of primary importance.

That year Marston & Smith (2001) responded to Brenner noting that his concern of blunting of the concept of 'scale' is valid since « scale is a produced societal metric that differentiates space; it is not space per se » (p. 615). But Brenner's dismissal of the household as scale led to a non-debate (Purcell, 2003) between the two. « It is simply arbitrary » they noted « that the home is relegated to a “place” or “arena”, while the state gets to be a multifaceted “scale” » (Marston & Smith, 2001, p. 618).4 They noted that « Geography needs analytic precision around scale, but they conclude that Brenner will not find the tools for that by maintaining boundaries between scalar production and the wider social production of space (à la Lefebvre) » (Jones et al., 2017, p. 146-147).

Five years later, Marston et al. (2005) published a paper in whose shadow the scalar debate still lives and a text which radically altered the terms of the debate. Marston et al. questioned the methodological efficacy and necessity of scale as an analytical concept. Marston et al.’s call for a human geography without scale was legitimated on the grounds that despite an acknowledgement of the networked view of scale across a range of works, there remained a tendency in the literature on scale to privilege a nested view of scale as there remained a « foundational hierarchy - a verticality that structures the nesting so central to the concept of scale » (p. 419). The three reasons they noted for challenging and doing away with the concept of scale were: 1) they argue that the distinction between size and level in scalar thinking is untenable, 2) that scale acts as a trojan horse to introduce the macro-micro distinction and 3) they note that various levels of scale are at the risk of becoming conceptual givens. Such a shift did not emerge out of a vacuum, as they themselves noted a set of works which argued for flat ontologies in their own distinct ways. However, as Jones et al., (2017) noted, this radical rejection of scale was already prefigured in Marston (2000), which had already suggested « the rejection of scale as an ontologically given category » (Marston, 2000, p. 220)”

Against scale, they prescribed a project engaged with flat ontology which is concerned with, 1) « analytics of composition and decomposition that resist the increasingly popular practice of representing the world as strictly a jumble of unfettered flow », 2) « attention to differential relations that constitute the driving forces of material composition and that problematize axiomatic tendencies to stratify and classify geographic objects » and 3) « a focus on localized and non-localized emergent events of differential relations actualized as temporary - often mobile – “sites” in which the “social” unfolds » (Marston et al., 2005, p. 423).

The publication of Marston et al. (2005) was followed by a range of responses. Leitner & Miller (2007) argued « Marston et al.’s “imaginary” critique of the scale literature points us only toward bordering practices as a technology of scale production » (p. 119) by privileging scale as size and misses out on the power relations that scale as levels highlights. They also noted that Marston et al. conflate hierarchy and verticality. The most explicit pro scale argument was levied by Jonas (2006) who argued that what he called « scalists » are responding « to the challenge of narrative and deploying scalar categories in ways that attempt to show how particular material structures and processes have become fixed at or around certain sites and scales, are in the process of becoming unfixed at a specific scale » (p. 404). Collinge (2006) who responded positively to the opening of this new debate noted that scale cannot be done away with swiftly as « by purging scale too hastily its replacement will remain within the metaphysical circuit, and within the spatial structuralism, from which it seeks to escape » (p. 251).

Authors concerned with this new threat of scale’s expurgation from the conceptual repertoire responded in various ways, wherein some introduced a methodological synthesis of territory, place, scale, network without privileging any of them (Jessop et al., 2008), the introduction of « phase space » (Jones, 2009), the call to overcome « scalar thought as incorporation » but not abandoning scale as an object of study (Isin, 2007), the call for planning theory to take up the challenge of immanent thinking (Hillier, 2008) among others.

There are political stakes in the scalar debate as Blakey (2020) suggests that « common-sense ideas about scale precede and shape social activity, working to frame time and space in different ways, along with what is seen as in and out of place. However, as our “common-sense” surrounding scales lacks an ontological principle, politics is always a possibility » (p. 13). Springer (2014a) though notes the political stakes which lie at the heart of Marston et al. (2005) explicitly, as a political disagreement between anarchist and Marxist influenced geographers.5 This difference, as Springer (2014a) notes, is at the heart of the debate’s political disagreement, one which takes the contemporary imaginaries and relationalities such as the state as worth engaging with, even if it wishes to reorder it while other practices a prefigurative politics. This political affinity is made explicit in the paper published two years after the 2005 paper wherein Marston et al., situate their project and thinking in affinity to the « style of zapatismo » (Jones et al., 2007, p. 275).

Concerning the Social: thinking of scale and social together

One of the goals of Marston et al.’s (2005) project, as noted before, was a call to study « “sites” in which the “social” unfolds » (p. 423). Leitner & Miller (2007) note that « site is the master spatial concept in Marston et al.’s flat ontology » (p. 120) and they go on to argue that « the flat ontology proposed by Marston et al. entails an a priori expurgation of scale » (p. 121). They note that the site-centric focus of actor-network theory (ANT) has been critiqued for its lack of theorization of power. Critiques of ANT have noted the lack of theorization around power and also affect (Müller & Schurr, 2016), but at the same time there do exist theorizations which try to think through power without abandoning the perspectives of ANT (see for example, Law, 1990).

I am more interested in the appearance of the ‘social’ in the above quote. The appearance of the ‘social’ necessities a discussion on this tangential interfacing of the scalar debate and the debates around social that have unfolded in the field of sociology, especially in the development of ANT. Interfacing the scalar concern and the concern of the social can be done through other thinkers and texts as well. Gidden’s theory of structuration is a common interface cited in other texts (Herod, 2010). From the annals of sociology in India, the work of Radhakamal Mukherjee (Mukerjee, 1930, 1932, 1960) can also be an interface. But Marston et al.’s radical questioning of the scale and this reference to the social makes it necessary to shift the focus to Latour’s (2005) instigation in sociology.

The ‘social’ has gone through sustained interrogation in the field of science and technology studies (STS) which has resulted in a precise ‘reassembling of the social’ in the field of Sociology by ANT (Latour, 2005). The anthropocentric biases of sociology have been laid bare over the past few decades (Pyyhtinen, 2016) which has resulted in re-thinking the primary question that forever haunts the disciple, « what is the social? » This shift in the discipline now clearly allows for an interfacing of sociology with geography explicitly.

Even though ANT had already reoriented a range of debates within STS, the publication of Latour’s Reassembling the Social marks the most elaborate and theoretical articulation of the project and addresses the discipline of sociology at large. The fundamental problematique that the book (Latour, 2005) addresses is that whenever an ethnographer studies local, sited, interaction they are inevitably led astray somewhere else to find context, most of the times towards a higher order of contextualization, towards the global, but after going far enough they are led back to the site again. One of the most usual argument for a retention of scale evokes a similar problematique of processes structuring the site and the individual (see Leitner & Miller, 2007, for example).

Latour (2005) classifies and categorizes two tendencies in sociology under what he calls « sociology of the social » and « sociology of associations ». He traces the genealogy of this distinction to the two early figures in sociology, Emile Durkheim and Gabriel Tarde, a genealogy and distinction I cannot develop here. But it is important to note these two figures in passing before elaborating the two tendencies, because it is Durkheim who ‘won’ over the discipline while Tarde’s writings still remain obscure and largely inaccessible in English.

« Tarde always complained that Durkheim had abandoned the task of explaining society by confusing cause and effect, replacing the understanding of the social link with a political project aimed at social engineering. Against his younger challenger, he vigorously maintained that the social was not a special domain of reality but a principle of connections; that there was no reason to separate “the social” from other associations like biological organisms or even atoms; that no break with philosophy, and especially meta-physics, was necessary in order to become a social science. » (Latour, 2005, p. 13)

Against the sociology of the social and critical sociology, Latour championed a project that was interested in tracing out associations in the field, to map the social, without arriving at explanations in the first place. Coupled with this, Latour demanded of sociology to not delineate the objects and processes that are considered valid in an a priori manner instead arguing for tracing associations in the social. This necessitated a turn away from the anthropocentric bias of sociology which had excommunicated non-human objects and processes from the domain of the social.

In Latour’s sociology of associations, one also finds a clear demarcation of a theory of scale. For Latour, « scale is what actors achieve by scaling, spacing, and contextualizing each other » (ibid, p. 183-184). As Jones et al. (2007) note, the project they envisioned in Marston et al. (2005) was different from ANT even while it was inspired by it and had shared affinity with the « Deleuzean difference » (Jones et al., 2007, p. 275). Instead of the above notion of scale that Latour argued for, Marston et al. (2005) argued for discarding of ‘scale’ as it inherently hierarchizes and stratifies instead arguing for site-specific elaborations. By doing so, they departed from Latour’s aforementioned suggestion while stressing and accentuating his argument that « the macro is neither “above” nor “below” the interactions, but added to them as another of their connections » (Latour, 2005, p. 177).

Latour insists that it is the « framing activity [...] of contextualizing, that should be brought into the foreground » (ibid, p. 186). Such an investigation, which interrogates the framing activities of actors, conceptualizes scale as frames of reference. It is in Legg (2009, 2011) that we find a clear association with the above Latourian concern of scale-as-frames and the processual signifier of scaling. While Latour used the signifier of scaling as something that actors do, Legg argued that the dual processes of descaling and rescaling are reconfigurations of relationalities of assemblages/apparatuses. Legg (2009, 2011) responded to Marston et al.’s dismissal of scale by arguing for a dual process of rescaling and descaling—by noting that scaling-effects are effects of assemblages and not frames. Saldanha (2017) in a far more emphatic reading of Marston et al. noted that in a certain sense Marston et al. are correct but stratifications do emerge and they matter as he noted, « assemblage opens on one side to the plane of consistency [...] on the other, to territories and structures that are [...] hierarchical and vectorial » (p. 99-100) while also noting the political imperative that, « scalarity is necessary for mapping the terrain on which social struggle is to take place » (p. 100).

In thinking through the scalar debate while engaged in fieldwork, I have come to the conclusion that scaling is a mode of contextualizing, as Latour notes, by situating and mobilizing a range of actors but it is also a bordering process, a process which values and evaluates the assemblages and their relation to other assemblages. I use the signifier of ‘assemblage’ here to stress on the interplay of material, discursive, affective processes6. Leitner & Miller (2007) noted against Marston et al. that bordering is not the primary attribute of scale, for example, nation-state has various other relationalities other than bordering. I agree here with them that bordering is not the only process that characterizes scaling. But I’m also suggesting that boundaries, however ephemeral or fuzzy, emerge for certain objects and processes to become coherent. I evoke the notion of valuation or evaluation in tandem with bordering to precisely mark that the sense of coherence of an object or process carries with it three notions of value that Graeber (2001) notes, as a conception « of what is [...] good », « the degree to which objects are desired » and « as “meaningful difference” » (p. 1-2). When Marston et al. (2005) and Springer (2014a) critique scale, it is precisely this notion of valuation vis-à-vis scale that they are uncomfortable with. As a sociologist or a geographer, scales must be approached with a degree of scepticism for this precise reason even if scale is not abandoned hastily as Collinge (2006) suggested.

Scaling, as I conceive of it, includes both the above ways of conceptualizing scale, scale as effect which includes the dual processes of rescaling and descaling and scale as framing. Legg’s (2009; 2011) dismissal of scale as frame by replacing it with scale as effects obscures the fact that frames are effects as well and do not emerge on a tabula rasa. Instead, by replacing the signifier of scale with scaling I’m stressing on the processual nature of the process. A rudimentary typology of processes that I have developed to locate scaling which includes scaling-effects i.e., processes resulting from relationality of matter, discourse, ideas, affects etc., which can also be frames one finds actors in the field deploying, are as follows:

- bordering - scaling creates boundaries between objects/processes,

- internal valuing - scaling orders the relationality of processes/objects within a particular assemblage

- external valuing - scaling orders the relationality of processes/objects/assemblage with other assemblages

Scaling then is a set of processes which engender valuations in the social, the cohering and coalescing of object and processes and their differentiation. While doing research, the researcher themselves, the actors, objects and processes that they study engender scaling. The three processes are immanent and hence parallel, and affect not just material objects/processes but also immaterial objects/processes. These valuations are constructed and also productive. By abstracting scaling to such processes, we do not just move away from the totalizing apparatuses of supposedly given scales such as ‘global’, ‘national’, ‘urban’, ‘domestic’, ‘Global South’ etc., but also open up our narratives and stories to mundane and ofttimes singular scaling processes. Scaling is what assemblages do and effect i.e., as conduits they coalesce to make certain bordering and valuing perceptible which gives a sense of scaling7. Against Brenner’s (2001) fear of diluting of scalar thinking by expanding the reach of the concept, I’m suggesting that it is precisely by casting the net of scalar thinking so wide and thin that we can map hitherto unmapped processes of scaling that one finds underway in the field. Instead of the wholesale dismissal of scale as Marston et al. (2005) intended, it would help to retain a minimalist concept of scale to map valuations and distinctions of places, sites, objects, processes etc. while being cognizant of the risks of scalar thinking that Marston et al. (2005) note.

If Latour desired a cartography of the ‘social’, we can also engage in a sociology of ‘scales’ i.e., an inquiry into relationalities of scaling, the association of various scaling-effects and scale-as-frame. The disciplines of sociology and geography do not appear so distant in such a view. The multitude of scalar stories and narratives and scalar processes of movement reveal the messiness of the ‘social’ which resist boxing into existing a priori scales.

The above approach has two effects. First, it allows for the dispelling of hegemonic scales such as the ‘national, ‘global’, ‘urban’, ‘regional’, etc., as natural and necessary allowing the researcher to abstract away from scales which are politically motivated, opening them to investigations. Second, it allows for an outlook which remains open to singular scales. The social under such a view suddenly appears as being constantly crisscrossed with scaling processes, valuations emerging in multitude.

Conclusion: A scalar reading of the scene

To go back to the scene that I began the paper with, the old man’s retort to my friend’s framing of Narayanpur as a mofussil is interesting precisely because it allows for an insight into how scaling manifests itself in the quotidian. Narayanpur, the neighbourhood in which we were having a conversation, is linked in that moment with New Town, the state, me having arrived from the city of Mumbai, my friend being a student at one of the better funded universities in the state in south Kolkata and also my friend having lived a considerable part of his life in Chandannagar.

This networked relationality of various sites, places, bodies led to a certain friction about the very nature of what constitutes a mofussil and a non-mofussil or to put it in other words, what constitutes the urban and non-urban. This friction can be read as a case of mobility (Cresswell, 2010), of our bodies arriving in Narayanpur one fine day without significant preparation, or it can also be read as a display of symbolic capital (Bourdieu, 1986), or a display of some status by noting a faculty of an university in the city who has returned to these obscure neighbourhoods, or an assertion of one’s civic pride (Collins, 2016), or as laying claim to the urbanization processes that are underway just a few kilometres away, but they all seek to explain the situation by looking elsewhere, as Latour (2005) notes. Instead, it is precisely by looking at the above interaction, or as Latour would put it, associations, that elucidate to us the fact that there is contestation concerning the very scalar categories of mofussil and non-mofussil and their reconfigurations, as scalar valuations.

As per the typology I laid out in the previous section, the old man in raising a controversy over what a mofussil is and where its boundaries are, where the boundaries of New Town are, and where/how the relationality of the state and the place manifests, scales these relationalities to determine boundaries and valuations of various sorts. At the same time, he is also trying to determine the internal and external relationalities, associations which crisscross these boundaries to evaluate the various objects and processes. He is deploying value in all of the three senses that I noted before, of what is good, desirable and to establish difference. By doing so he is scaling New Town, mofussil and all other objects and other associated processes.

Because the scene that I have chosen is a quotidian conversation, it is easier to get a sense of the process of scale-as-frame’. But it would be wrong to suggest that scale-as-effect is missing in the above scene. The frames that the two individuals deploy are a consequence i.e., an effect of a range of overdetermined processes, one being the planning and development of New Town which is what I wanted to initially comprehend. For a lack of space, I cannot delve into the planning and development of New Town. But it would be suffice to note that New Town’s planning and development has been noted to be a process of primitive accumulation (Bhattacharya & Sanyal, 2011) to instigate capital's movement for the real estate sector (Dey et al., 2016) and later the information technology sector (Mitra, 2013) while the governmental documents attest an environmental concern and unplanned private realty growth as the foundational justification (Ghosh Bose & Associates Pvt. Ltd., 1999; West Bengal Housing Infrastructure Development Corporation, 1999). While such particular processes led to the planning and development of New Town, New Town can also be situated against a more general and longer trend of the eastward expansion of the Kolkata urban agglomeration (Bhattacharya & Sanyal, 2011; Chakravorty & Gupta, 1996; Chattopadhyaya, 1990; Roy, 2002). The associations keep unravelling if one keeps following them and that is precisely what scalar thinking which deploys scaffoldings and sociological investigations which consider only certain objects and processes as valid ‘social’ entities foreclose.

To erase scaling and its common-sensical notion in the above scene, to arrive at the above scene with pre-existing scales or to explain it away by looking elsewhere would be to obfuscate the controversy of scalar thinking and associations that the old man in the scene is raising. It is precisely in moments such as these that sociology and geography can interface, where a cartography of the social and a sociology of scales can be mobilized. To trace associations and valuations about human and non-human processes is at the heart of this interfacing. To shy away from them by resorting to scaffoldings is not just to be unimaginative but also politically dishonest in cordoning off the terrain that practitioners of the discipline can pursue. As geographers trace associations, so the sociologists spatialize the associations.